State Church Of The Roman Empire on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor

in The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. Retrieved 19 July 2010 On the contrary, "in the East Roman or Byzantine view, when the Roman Empire became Christian, the perfect world order willed by God had been achieved: one universal empire was sovereign, and coterminous with it was the one universal church"; and the church came, by the time of the demise of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, to merge psychologically with it to the extent that its bishops had difficulty in thinking of Nicene Christianity without an emperor.Schadé (2006), art. "Byzantine Church" The legacy of the idea of a universal church carries on in today's Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the

Before the end of the 1st century, the Roman authorities recognized Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. The distinction, perhaps already made in practice at the time of the

Before the end of the 1st century, the Roman authorities recognized Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. The distinction, perhaps already made in practice at the time of the

On 27 February of the previous year, Theodosius I established, with the

On 27 February of the previous year, Theodosius I established, with the

At the end of the 4th century the Roman Empire had effectively split into two parts although their economies and the imperial-recognized church were still strongly tied. The two halves of the empire had always had cultural differences, exemplified in particular by the widespread use of the

At the end of the 4th century the Roman Empire had effectively split into two parts although their economies and the imperial-recognized church were still strongly tied. The two halves of the empire had always had cultural differences, exemplified in particular by the widespread use of the  The 5th century would see the further fracturing of Christendom. Emperor

The 5th century would see the further fracturing of Christendom. Emperor

In the 5th century, the Western Empire rapidly decayed and by the end of the century was no more. Within a few decades,

In the 5th century, the Western Empire rapidly decayed and by the end of the century was no more. Within a few decades,

Emperor

Emperor

The Rashidun conquests began to expand the sway of

The Rashidun conquests began to expand the sway of

During the

During the  Of these, the Church in Great Moravia chose immediately to link with Rome, not Constantinople: the missionaries sent there sided with the Pope during the

Of these, the Church in Great Moravia chose immediately to link with Rome, not Constantinople: the missionaries sent there sided with the Pope during the

With the defeat and death in 751 of the last

With the defeat and death in 751 of the last

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also called Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. During his reign, he succeeded in a crucial war against the Goths, as well as in two ...

issued the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholic (term), Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds s ...

in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

in the Great Church

The term "Great Church" ( la, ecclesia magna) is used in the historiography of early Christianity to mean the period of about 180 to 313, between that of primitive Christianity and that of the legalization of the Christian religion in the Roman ...

as the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

's state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

. Most historians refer to the Nicene church associated with emperors in a variety of ways: as the catholic church, the orthodox church, the imperial church, the imperial Roman church, or the Byzantine church, although some of those terms are also used for wider communions extending outside the Roman Empire. The Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

, Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

, and the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, all claim to stand in continuity from the Nicene church to which Theodosius granted recognition.

Earlier in the 4th century, following the Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

of 303–313 and the Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and the ...

controversy that arose in consequence, Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to Constantine the Great and Christianity, convert to Christiani ...

had convened councils of bishops to define the orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

of the Christian faith and to expand on earlier Christian councils. A series of ecumenical councils

An ecumenical council, also called general council, is a meeting of bishops and other church authorities to consider and rule on questions of Christian doctrine, administration, discipline, and other matters in which those entitled to vote ar ...

convened by successive Roman emperors met during the 4th and the 5th centuries, but Christianity continued to suffer rifts and schisms surrounding the theological

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

and christological

In Christianity, Christology (from the Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, -λογία, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Christ", is a branch of theology that concerns Jesus. Di ...

doctrines of Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

, Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

, and Miaphysitism

Miaphysitism is the Christological doctrine that holds Jesus, the "Incarnate Word, is fully divine and fully human, in one 'nature' (''physis'')." It is a position held by the Oriental Orthodox Churches and differs from the Chalcedonian positio ...

. In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

decayed as a polity

A polity is an identifiable Politics, political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of Institutionalisation, institutionalized social relation, social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize ...

; invaders sacked Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

in 410 and in 455, and Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus Augustul ...

, an Arian barbarian warlord, forced Romulus Augustus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time, ...

, the last nominal Western Emperor, to abdicate in 476. However, apart from the aforementioned schisms, the church as an institution persisted in communion, if not without tension, between the East

East or Orient is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fa ...

and West

West or Occident is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sunset, Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic languages, German ...

. In the 6th century, the Byzantine armies of the Byzantine Emperor

This is a list of the Byzantine emperors from the foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD, which marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, to its fall to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as le ...

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

recovered Italy and other regions of the Western Mediterranean shore. The Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

soon lost most of these gains, but it held Rome, as part of the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

, until 751, a period known in church history

__NOTOC__

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritua ...

as the Byzantine Papacy

The Byzantine Papacy was a period of Byzantine domination of the Roman papacy from 537 to 752, when popes required the approval of the Byzantine Emperor for episcopal consecration, and many popes were chosen from the '' apocrisiarii'' (liaisons ...

. The early Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 7th–9th centuries would begin a process of converting most of the then-Christian world in the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, regions of Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the peop ...

and the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula (),

**

* Aragonese and Occitan: ''Peninsula Iberica''

**

**

* french: Péninsule Ibérique

* mwl, Península Eibérica

* eu, Iberiar penintsula also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in southwestern Europe, defi ...

to Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

, severely restricting the reach both of the Byzantine Empire and of its church. Christian missionary activity directed from the capital of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

did not lead to a lasting expansion of the formal link between the church and the Byzantine emperor, since areas outside the Byzantine Empire's political and military control set up their own distinct churches, as in the case of Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

in 919.

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

, who became emperor in 527, recognized the patriarch

The highest-ranking bishops in Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church (above major archbishop and primate), the Hussite Church, Church of the East, and some Independent Catholic Churches are termed patriarchs (and in certai ...

s of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

, and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

as the supreme authorities in the state-sponsored Chalcedonian

Chalcedonian Christianity is the branch of Christianity that accepts and upholds theological and ecclesiological resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, held in 451. Chalcedonian Christianity accepts the Christolo ...

church apparatus (see the Pentarchy

Pentarchy (from the Greek , ''Pentarchía'', from πέντε ''pénte'', "five", and ἄρχειν ''archein'', "to rule") is a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I (527–565) of the Roman Empire. In this ...

). However, Justinian claimed " the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church".

In Justinian's day, the Christian church was not entirely under the emperor's control even in the East: the Oriental Orthodox Churches had seceded, having rejected the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

in 451, and called the adherents of the imperially-recognized church "Melkite

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christianity, Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic Semitic root, ro ...

s", from Syriac ''malkâniya'' ("imperial"). In Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's countries and territories vary depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the ancient Mediterranean ...

, Christianity was mostly subject to the laws and customs of nations that owed no allegiance to the emperor in Constantinople.Ayer (1913), pp. 538–539 While Eastern-born popes appointed or at least confirmed by the emperor continued to be loyal to him as their political lord, they refused to accept his authority in religious matters, or the authority of such a council as the imperially convoked Council of Hieria

The iconoclast Council of Hieria was a Christian council of 754 which viewed itself as ecumenical, but was later rejected by the Second Council of Nicaea (787) and by Catholic and Orthodox churches, since none of the five major patriarchs were ...

of 754. Pope Gregory III

Pope Gregory III ( la, Gregorius III; died 28 November 741) was the bishop of Rome from 11 February 731 to his death. His pontificate, like that of his predecessor, was disturbed by Byzantine iconoclasm and the advance of the Lombards, in which ...

(731–741) was the last Bishop of Rome to ask the Byzantine ruler to ratify his election. With the crowning of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

by Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

on 25 December

Events Pre-1600

* 36 – Forces of Emperor Guangwu of the Eastern Han, under the command of Wu Han, conquer the separatist Chengjia empire, reuniting China.

* 274 – A temple to Sol Invictus is dedicated in Rome by Emperor Aurel ...

800 as '' Imperator Romanorum'', the political split between East and West became irrevocable. Spiritually, Chalcedonian Christianity

Chalcedonian Christianity is the branch of Christianity that accepts and upholds theological and ecclesiological resolutions of the Council of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, held in 451. Chalcedonian Christianity accepts the Christolo ...

persisted, at least in theory, as a unified entity until the Great Schism and its formal division with the mutual excommunication in 1054 of Rome and Constantinople. The empire finally collapsed with the Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

to the Islamic Ottoman Turks

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

in 1453.

The obliteration of the empire's boundaries by Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

and an outburst of missionary activity among these peoples, who had no direct links with the empire, and among Pictic and Celtic peoples

The Celts (, see Names of the Celts#Pronunciation, pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-Europea ...

who had never been part of the Roman Empire, fostered the idea of a universal church free from association with a particular state.Gerland, Ernst. "The Byzantine Empire"in The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. Retrieved 19 July 2010 On the contrary, "in the East Roman or Byzantine view, when the Roman Empire became Christian, the perfect world order willed by God had been achieved: one universal empire was sovereign, and coterminous with it was the one universal church"; and the church came, by the time of the demise of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, to merge psychologically with it to the extent that its bishops had difficulty in thinking of Nicene Christianity without an emperor.Schadé (2006), art. "Byzantine Church" The legacy of the idea of a universal church carries on in today's Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, and the

Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

. Many other churches, such as the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, claim succession to this universal church.

History

Early Christianity in relation to the state

Before the end of the 1st century, the Roman authorities recognized Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. The distinction, perhaps already made in practice at the time of the

Before the end of the 1st century, the Roman authorities recognized Christianity as a separate religion from Judaism. The distinction, perhaps already made in practice at the time of the Great Fire of Rome

The Great Fire of Rome ( la, incendium magnum Romae) occurred in July AD 64. The fire began in the merchant shops around Rome's chariot stadium, Circus Maximus, on the night of 19 July. After six days, the fire was brought under control, but before ...

in the year 64, was given official status by the emperor Nerva

Nerva (; originally Marcus Cocceius Nerva; 8 November 30 – 27 January 98) was Roman emperor from 96 to 98. Nerva became emperor when aged almost 66, after a lifetime of imperial service under Nero and the succeeding rulers of the Flavian dy ...

around the year 98 by granting Christians exemption from paying the ''Fiscus Iudaicus

The or (Latin for "Jewish tax") was a Roman Empire#Taxation, tax imposed on History of the Jews in the Roman Empire, Jews in the Roman Empire after the Siege of Jerusalem (70), destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple in AD 70. Revenues were d ...

'', the annual tax upon the Jews. Pliny the Younger, when propraetor

In ancient Rome a promagistrate ( la, pro magistratu) was an ex-consul or ex-praetor whose ''imperium'' (the power to command an army) was extended at the end of his annual term of office or later. They were called proconsuls and propraetors. Thi ...

in Bithynia

Bithynia (; Koine Greek: , ''Bithynía'') was an ancient region, kingdom and Roman province in the northwest of Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), adjoining the Sea of Marmara, the Bosporus, and the Black Sea. It bordered Mysia to the southwest, Pa ...

in 103, assumes in his letters to Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presi ...

that because Christians do not pay the tax, they are not Jews.Wylen (1995). pp. 190–192.Dunn (1999). pp. 33–34.Boatwright (2004). p. 426.

Since paying taxes had been one of the ways that Jews demonstrated their goodwill and loyalty toward the empire, Christians had to negotiate their own alternatives to participating in the imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor or a dynasty of emperors (or rulers of another title) are worshipped as demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense. The cult may ...

. Their refusal to worship the Roman gods

The Roman deities most widely known today are those the Romans identified with Greek counterparts (see ''interpretatio graeca''), integrating Greek myths, iconography, and sometimes religious practices into Roman culture, including Latin lite ...

or to pay homage to the emperor as divine resulted at times in persecution and martyrdom. Church Father

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical pe ...

Tertullian

Tertullian (; la, Quintus Septimius Florens Tertullianus; 155 AD – 220 AD) was a prolific early Christian author from Carthage in the Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive corpus of L ...

, for instance, attempted to argue that Christianity was not inherently treasonous, and that Christians could offer their own form of prayer for the well-being of the emperor.

Christianity spread especially in the eastern parts of the empire and beyond its border; in the west it was at first relatively limited, but significant Christian communities emerged in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

, and other urban centers, becoming by the end of the 3rd century

The 3rd century was the period from 201 ( CCI) to 300 (CCC) Anno Domini (AD) or Common Era (CE) in the Julian calendar..

In this century, the Roman Empire saw a crisis, starting with the assassination of the Roman Emperor Severus Alexander ...

, the dominant faith in some of them. Christians accounted for approximately 10% of the Roman population by 300, according to some estimates. According to Will Durant

William James Durant (; November 5, 1885 – November 7, 1981) was an American writer, historian, and philosopher. He became best known for his work '' The Story of Civilization'', which contains 11 volumes and details the history of eastern a ...

, the Christian Church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

prevailed over paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christianity, early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions ot ...

because it offered a much more attractive doctrine and because the church leaders addressed human needs better than their rivals.Durant, Will. Caesar and Christ. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1972

In 301, the Kingdom of Armenia, nominally a Roman client kingdom but ruled by a Parthian Parthian may be:

Historical

* A demonym "of Parthia", a region of north-eastern of Greater Iran

* Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD)

* Parthian language, a now-extinct Middle Iranian language

* Parthian shot, an archery skill famously employed by ...

dynasty, became the first nation to adopt Christianity as its state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

.

Establishment and early controversies

In 311, with theEdict of Serdica

The Edict of Serdica, also called Edict of Toleration by Galerius, was issued in 311 in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) by Roman Emperor Galerius. It officially ended the Diocletianic Persecution of Christianity in the Eastern Roman Empire.

The E ...

the dying Emperor Galerius

Gaius Galerius Valerius Maximianus (; 258 – May 311) was Roman emperor from 305 to 311. During his reign he campaigned, aided by Diocletian, against the Sasanian Empire, sacking their capital Ctesiphon in 299. He also campaigned across the D ...

ended the Diocletianic Persecution

The Diocletianic or Great Persecution was the last and most severe persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire. In 303, the emperors Diocletian, Maximian, Galerius, and Constantius issued a series of edicts rescinding Christians' legal rights ...

that he is reputed to have instigated, and in 313, Emperor Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

issued the Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan ( la, Edictum Mediolanense; el, Διάταγμα τῶν Μεδιολάνων, ''Diatagma tōn Mediolanōn'') was the February 313 AD agreement to treat Christians benevolently within the Roman Empire. Frend, W. H. C. ( ...

, granting to Christians and others "the right of open and free observance of their worship".

Constantine began to utilize Christian symbols such as the Chi Rho early in his reign but still encouraged traditional Roman religious practices including sun worship. In 330, Constantine established the city of Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

as the new capital of the Roman Empire. The city would gradually come to be seen as the intellectual and cultural center of the Christian world

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

.

Over the course of the 4th century the Christian body became consumed by debates surrounding orthodoxy

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

, i.e. which religious doctrines are the correct ones. In the early 4th century, a group in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, later called Donatists, who believed in a very rigid interpretation of Christianity that excluded many who had abandoned the faith during the Diocletianic Persecution, created a crisis in the western empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period fr ...

.

A synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word ''wikt:synod, synod'' comes from the meaning "assembly" or "meeting" and is analogous with the Latin ...

was held in Rome in 313, followed by another in Arles in 314. These synods ruled that the Donatist faith was heresy and, when the Donatists refused to recant, Constantine launched the first campaign of persecution by Christians against Christians, and began imperial involvement in Christian theology. However, during the reign of Emperor Julian the Apostate, the Donatists, who formed the majority party in the Roman province of Africa for 30 years, were given official approval.

Debates within Christianity

Christian scholars and populace within the empire were increasingly embroiled in debates regardingchristology

In Christianity, Christology (from the Ancient Greek, Greek grc, Χριστός, Khristós, label=none and grc, wiktionary:-λογία, -λογία, wiktionary:-logia, -logia, label=none), translated literally from Greek as "the study of Chr ...

(i.e., regarding the nature of the Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, names and titles), was ...

). Opinions ranged from belief that Jesus was entirely human to belief that he was entirely divine. The most persistent debate was that between the homoousian

Homoousion ( ; grc, ὁμοούσιον, lit=same in being, same in essence, from , , "same" and , , "being" or "essence") is a Christian theological term, most notably used in the Nicene Creed for describing Jesus (God the Son) as "same in b ...

view (the Father and the Son are of one substance), defined at the Council at Nicaea in 325 and later championed by Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria, ; cop, ⲡⲓⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲡⲓⲁⲡⲟⲥⲧⲟⲗⲓⲕⲟⲥ or Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ ⲁⲑⲁⲛⲁⲥⲓⲟⲩ ⲁ̅; (c. 296–298 – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, ...

, and the Arian view (the Father and the Son are similar, but the Father is greater than the Son). Emperors thereby became ever more involved with the increasingly divided early Church.

Constantine backed the Nicene Creed of Nicaea, but was baptized on his deathbed by the Eusebius of Nicomedia, a bishop with Arian sympathies. His successor Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germani ...

supported Arian positions: under his rule, the Council of Constantinople in 360 supported the Arian view. After the interlude of Emperor Julian, who wanted to return to the pagan Roman/Greek religion, the west stuck to the Nicene Creed, while Arianism or Semi-Arianism

Semi-Arianism was a position regarding the relationship between God the Father and the Son of God, adopted by some 4th-century Christians. Though the doctrine modified the teachings of Arianism, it still rejected the doctrine that Father, Son, ...

was dominant in the east (under Emperor Valens), until Emperor Theodosius I called the Council of Constantinople in 381, which reasserted the Nicene view and rejected the Arian view. This council further refined the definition of orthodoxy, issuing the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is a ...

. On 27 February of the previous year, Theodosius I established, with the

On 27 February of the previous year, Theodosius I established, with the Edict of Thessalonica

The Edict of Thessalonica (also known as ''Cunctos populos''), issued on 27 February AD 380 by Theodosius I, made the Catholic (term), Catholicism of Nicene Christians the state church of the Roman Empire.

It condemned other Christian creeds s ...

, the Christianity of the First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

as the official state religion

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular state, secular, is not n ...

, reserving for its followers the title of Catholic Christians and declaring that those who did not follow the religion taught by Pope Damasus I

Pope Damasus I (; c. 305 – 11 December 384) was the bishop of Rome from October 366 to his death. He presided over the Council of Rome of 382 that determined the canon or official list of sacred scripture. He spoke out against major heresies ( ...

of Rome and Pope Peter of Alexandria were to be called heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

:

In 391, Theodosius closed all the "pagan" (non-Christian and non-Jewish) temples and formally forbade pagan worship.

Late antiquity

At the end of the 4th century the Roman Empire had effectively split into two parts although their economies and the imperial-recognized church were still strongly tied. The two halves of the empire had always had cultural differences, exemplified in particular by the widespread use of the

At the end of the 4th century the Roman Empire had effectively split into two parts although their economies and the imperial-recognized church were still strongly tied. The two halves of the empire had always had cultural differences, exemplified in particular by the widespread use of the Greek language

Greek ( el, label=Modern Greek, Ελληνικά, Elliniká, ; grc, Ἑλληνική, Hellēnikḗ) is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages, native to Greece, Cyprus, southern Italy (Calabria and Salento), southern Al ...

in the Eastern Empire and its more limited use in the West (Greek, as well as Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

, was used in the West, but Latin was the spoken vernacular

A vernacular or vernacular language is in contrast with a "standard language". It refers to the language or dialect that is spoken by people that are inhabiting a particular country or region. The vernacular is typically the native language, n ...

).

By the time Christianity became the state religion of the empire at the end of the 4th century, scholars in the West had largely abandoned Greek in favor of Latin. Even the Church in Rome, where Greek continued to be used in the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. ''Liturgy'' can also be used to refer specifically to public worship by Christians. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and partic ...

longer than in the provinces, abandoned Greek. Jerome

Jerome (; la, Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος Σωφρόνιος Ἱερώνυμος; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was a Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, th ...

's Vulgate

The Vulgate (; also called (Bible in common tongue), ) is a late-4th-century Latin translation of the Bible.

The Vulgate is largely the work of Jerome who, in 382, had been commissioned by Pope Damasus I to revise the Gospels u ...

had begun to replace the older Latin translations of the Bible.

The 5th century would see the further fracturing of Christendom. Emperor

The 5th century would see the further fracturing of Christendom. Emperor Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

called two synods in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, one in 431 and one in 449, the first of which condemned the teachings of Patriarch Nestorius

Nestorius (; in grc, Νεστόριος; 386 – 451) was the Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to August 431. A Christian theologian, several of his teachings in the fields of Christology and Mariology were seen as controve ...

of Constantinople, while the second supported the teachings of Eutyches

Eutyches ( grc, Εὐτυχής; c. 380c. 456) or Eutyches of ConstantinopleArchbishop Flavian of Constantinople

Flavian ( la, Flavianus; grc-gre, Φλαβιανος, ''Phlabianos''; 11 August 449), sometimes Flavian I, was Archbishop of Constantinople from 446 to 449. He is venerated as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Ch ...

.Price (2005), p. 52

Nestorius taught that Christ's divine and human nature were distinct persons, and hence Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

was the mother of Christ but not the mother of God. Eutyches taught on the contrary that there was in Christ only a single nature, different from that of human beings in general. The First Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperors, Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus deci ...

rejected Nestorius' view, causing churches centered around the School of Edessa, a city at the edge of the empire, to break with the imperial church (see Nestorian schism).

Persecuted within the Roman Empire, many Nestorians fled to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and joined the Sassanid

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

Church (the future Church of the East

The Church of the East ( syc, ܥܕܬܐ ܕܡܕܢܚܐ, ''ʿĒḏtā d-Maḏenḥā'') or the East Syriac Church, also called the Church of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Persian Church, the Assyrian Church, the Babylonian Church or the Nestorian C ...

). The Second Council of Ephesus

The Second Council of Ephesus was a Christological church synod in 449 AD convened by Emperor Theodosius II under the presidency of Pope Dioscorus I of Alexandria. It was intended to be an ecumenical council, and it is accepted as such by the ...

upheld the view of Eutyches, but was overturned two years later by the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

, called by Emperor Marcian. Rejection of the Council of Chalcedon led to the exodus from the state church of the majority of Christians in Egypt and many in the Levant, who preferred Miaphysite theology.

Thus, within a century of the link established by Theodosius between the emperor and the church in his empire, it suffered a significant diminishment. Those who upheld the Council of Chalcedon became known in Syriac Syriac may refer to:

*Syriac language, an ancient dialect of Middle Aramaic

*Sureth, one of the modern dialects of Syriac spoken in the Nineveh Plains region

* Syriac alphabet

** Syriac (Unicode block)

** Syriac Supplement

* Neo-Aramaic languages a ...

as Melkites

The term Melkite (), also written Melchite, refers to various Eastern Christian churches of the Byzantine Rite and their members originating in the Middle East. The term comes from the common Central Semitic root ''m-l-k'', meaning "royal", and ...

, the ''imperial'' group, followers of the ''emperor'' (in Syriac, ''malka''). This schism resulted in an independent communion of churches, including the Egyptian, Syrian, Ethiopian and Armenian churches, that is today known as Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent ...

. In spite of these schisms, however, the Chalcedonian Nicene church still represented the majority of Christians within the by now already diminished Roman Empire.

End of the Western Roman Empire

In the 5th century, the Western Empire rapidly decayed and by the end of the century was no more. Within a few decades,

In the 5th century, the Western Empire rapidly decayed and by the end of the century was no more. Within a few decades, Germanic tribes

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

, particularly the Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Europe ...

and Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic peoples, Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal Kingdom, Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The ...

, conquered the western provinces. Rome was sacked in 410 and 455, and was to be sacked again in the following century in 546.

By 476, the Germanic chieftain Odoacer

Odoacer ( ; – 15 March 493 AD), also spelled Odovacer or Odovacar, was a soldier and statesman of barbarian background, who deposed the child emperor Romulus Augustulus and became Rex/Dux (476–493). Odoacer's overthrow of Romulus Augustul ...

had conquered Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and deposed the last western emperor, Romulus Augustus

Romulus Augustus ( 465 – after 511), nicknamed Augustulus, was Roman emperor of the West from 31 October 475 until 4 September 476. Romulus was placed on the imperial throne by his father, the ''magister militum'' Orestes, and, at that time, ...

, though he nominally submitted to the authority of Constantinople. The Arian Germanic tribes established their own systems of churches and bishops in the western provinces but were generally tolerant of the population who chose to remain in communion with the imperial church.

In 533, Roman Emperor Justinian

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

in Constantinople launched a military campaign to reclaim the western provinces from the Arian Germans, starting with North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

and proceeding to Italy. His success in recapturing much of the western Mediterranean was temporary. The empire soon lost most of these gains, but held Rome, as part of the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

, until 751.

Justinian definitively established Caesaropapism

Caesaropapism is the idea of combining the social and political power of secular government with religious power, or of making secular authority superior to the spiritual authority of the Church; especially concerning the connection of the Chur ...

,Ayer (1913), p. 538 believing "he had the right and duty of regulating by his laws the minutest details of worship and discipline, and also of dictating the theological opinions to be held in the Church".Ayer (1913), p. 553 According to the entry in Liddell & Scott

Liddell is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Alice Liddell (1852–1934), Lewis Carroll's "muse"

* Allan Liddell (1908–1970)

* Alvar Lidell (1908–1981), BBC radio announcer and newsreader

* Andreas Lidel (1740s–1780s), co ...

, the term ''orthodox

Orthodox, Orthodoxy, or Orthodoxism may refer to:

Religion

* Orthodoxy, adherence to accepted norms, more specifically adherence to creeds, especially within Christianity and Judaism, but also less commonly in non-Abrahamic religions like Neo-pa ...

'' first occurs in the Codex Justinianus

The Code of Justinian ( la, Codex Justinianus, or ) is one part of the ''Corpus Juris Civilis'', the codification of Roman law ordered early in the 6th century AD by Justinian I, who was Eastern Roman emperor in Constantinople. Two other units, t ...

: "We direct that all Catholic churches, throughout the entire world, shall be placed under the control of the orthodox bishops who have embraced the Nicene Creed."

By the end of the 6th century the church within the Empire had become firmly tied with the imperial government, while in the west Christianity was mostly subject to the laws and customs of nations that owed no allegiance to the emperor.

Patriarchates in the Empire

Emperor

Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovat ...

assigned to five sees, those of Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

, Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandria ...

, Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

and Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

, a superior ecclesial authority that covered the whole of his empire. The First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea (; grc, Νίκαια ) was a council of Christian bishops convened in the Bithynian city of Nicaea (now İznik, Turkey) by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325.

This ecumenical council was the first effort ...

in 325 reaffirmed that the bishop of a provincial capital, the metropolitan bishop, had a certain authority over the bishops of the province. But it also recognized the existing supra-metropolitan authority of the sees of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, and granted special recognition to Jerusalem.

Constantinople was added at the First Council of Constantinople

The First Council of Constantinople ( la, Concilium Constantinopolitanum; grc-gre, Σύνοδος τῆς Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) was a council of Christian bishops convened in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) in AD 381 b ...

(381) and given authority initially only over Thrace

Thrace (; el, Θράκη, Thráki; bg, Тракия, Trakiya; tr, Trakya) or Thrake is a geographical and historical region in Southeast Europe, now split among Bulgaria, Greece, and Turkey, which is bounded by the Balkan Mountains to t ...

. By a canon of contested validity, the Council of Chalcedon

The Council of Chalcedon (; la, Concilium Chalcedonense), ''Synodos tēs Chalkēdonos'' was the fourth ecumenical council of the Christian Church. It was convoked by the Roman emperor Marcian. The council convened in the city of Chalcedon, Bith ...

(451) placed Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

and Pontus

Pontus or Pontos may refer to:

* Short Latin name for the Pontus Euxinus, the Greek name for the Black Sea (aka the Euxine sea)

* Pontus (mythology), a sea god in Greek mythology

* Pontus (region), on the southern coast of the Black Sea, in modern ...

, which together made up Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

, under Constantinople, although their autonomy had been recognized at the council of 381.

Rome never recognized this pentarchy

Pentarchy (from the Greek , ''Pentarchía'', from πέντε ''pénte'', "five", and ἄρχειν ''archein'', "to rule") is a model of Church organization formulated in the laws of Emperor Justinian I (527–565) of the Roman Empire. In this ...

of five sees as constituting the leadership of the church. It maintained that, in accordance with the First Council of Nicaea, only the three " Petrine" sees of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch had a real patriarchal function. The canons of the Quinisext Council

The Quinisext Council (Latin: ''Concilium Quinisextum''; Koine Greek: , ''Penthékti Sýnodos''), i.e. the Fifth-Sixth Council, often called the Council ''in Trullo'', Trullan Council, or the Penthekte Synod, was a church council held in 692 at ...

of 692, which gave ecclesiastical sanction to Justinian's decree, were also never fully accepted by the Western Church.

Early Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the territories of the patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, most of whose Christians were in any case lost to the orthodox church since the aftermath of the Council of Chalcedon, left in effect only two patriarchates, those of Rome and Constantinople. In 732, Emperor Leo III's iconoclast

Iconoclasm (from Greek: grc, εἰκών, lit=figure, icon, translit=eikṓn, label=none + grc, κλάω, lit=to break, translit=kláō, label=none)From grc, εἰκών + κλάω, lit=image-breaking. ''Iconoclasm'' may also be conside ...

policies were resisted by Pope Gregory III

Pope Gregory III ( la, Gregorius III; died 28 November 741) was the bishop of Rome from 11 February 731 to his death. His pontificate, like that of his predecessor, was disturbed by Byzantine iconoclasm and the advance of the Lombards, in which ...

. The Emperor reacted by transferring to the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Constantinople in 740 the territories in Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, Illyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria (; grc, Ἰλλυρία, ''Illyría'' or , ''Illyrís''; la, Illyria, ''Illyricum'') was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by numerous tribes of people collectively known as the Illyr ...

, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

and Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

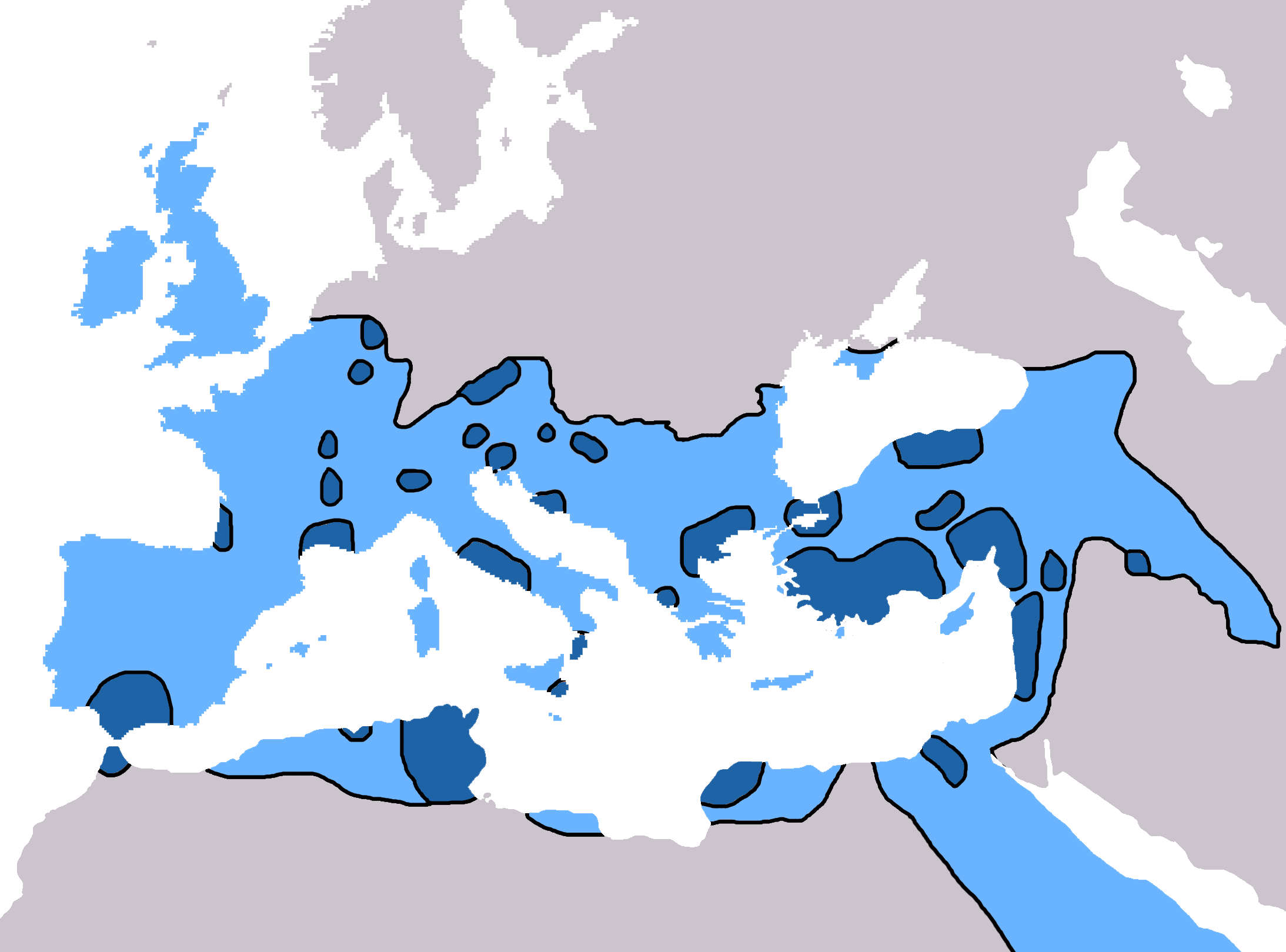

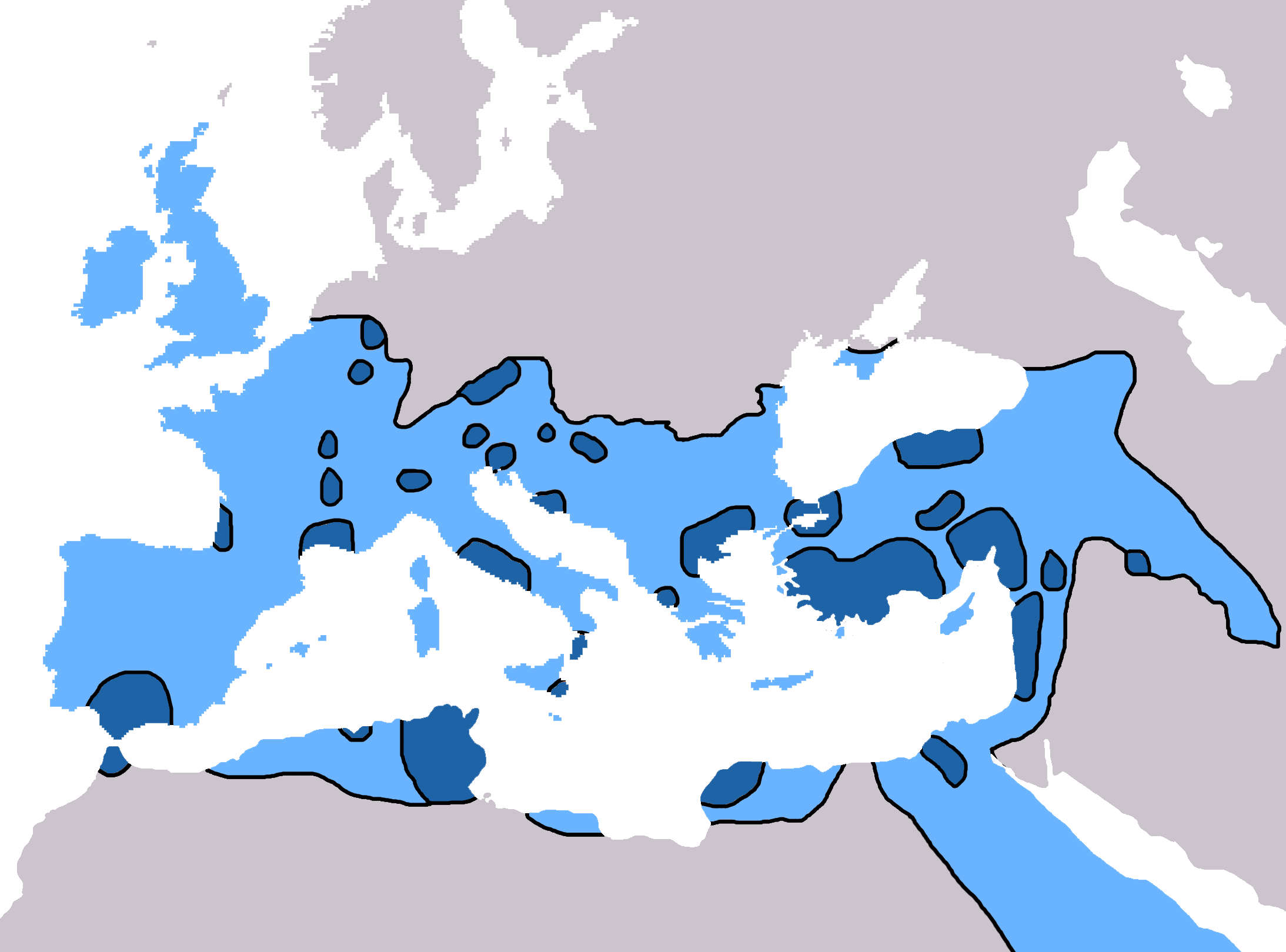

that had been under Rome (see map), leaving the bishop of Rome with only a minute part of the lands over which the empire still had control.

The Patriarch of Constantinople had already adopted the title of "ecumenical patriarch", indicating what he saw as his position in the ''oikoumene'', the Christian world ideally headed by the emperor and the patriarch of the emperor's capital. Also under the influence of the imperial model of governance of the state church, in which "the emperor becomes the actual executive organ of the universal Church", the pentarchy model of governance of the state church regressed to a monarchy of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Rise of Islam

The Rashidun conquests began to expand the sway of

The Rashidun conquests began to expand the sway of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic Monotheism#Islam, monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God in Islam, God (or ...

beyond Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

in the 7th century, first clashing with the Roman Empire in 634. That empire and the Sassanid Persian Empire were at that time crippled by decades of war between them. By the late 8th century the Umayyad caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

had conquered all of Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and much of the Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

territory including Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Palestine, and Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

.

Suddenly, much of the Christian world was under Muslim rule. Over the coming centuries the successive Muslim states became some of the most powerful in the Mediterranean world.

Though the Byzantine church claimed religious authority over Christians in Egypt and the Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

, in reality the majority of Christians in these regions were by then miaphysites and members of other sects. The new Muslim rulers, in contrast, offered religious tolerance to Christians of all sects. Additionally subjects of the Muslim Empire could be accepted as Muslims simply by declaring a belief in a single deity and reverence for Muhammad (see shahada

The ''Shahada'' (Arabic: ٱلشَّهَادَةُ , "the testimony"), also transliterated as ''Shahadah'', is an Islamic oath and creed, and one of the Five Pillars of Islam and part of the Adhan. It reads: "I bear witness that there is n ...

). As a result, the peoples of Egypt, Palestine and Syria largely accepted their new rulers and many declared themselves Muslims within a few generations. Muslim incursions later found success in parts of Europe, particularly Spain (see Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus DIN 31635, translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label=Berber languages, Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, ...

).

Expansion of Christianity in Europe

During the

During the 9th century

The 9th century was a period from 801 ( DCCCI) through 900 ( CM) in accordance with the Julian calendar.

The Carolingian Renaissance and the Viking raids occurred within this period. In the Middle East, the House of Wisdom was founded in Abba ...

, the Emperor in Constantinople encouraged missionary expeditions to nearby nations including the Muslim caliphate, and the Turkic Khazars

The Khazars ; he, כּוּזָרִים, Kūzārīm; la, Gazari, or ; zh, 突厥曷薩 ; 突厥可薩 ''Tūjué Kěsà'', () were a semi-nomadic Turkic people that in the late 6th-century CE established a major commercial empire coverin ...

. In 862 he sent Saints Cyril and Methodius

Cyril (born Constantine, 826–869) and Methodius (815–885) were two brothers and Byzantine Christian theologians and missionaries. For their work evangelizing the Slavs, they are known as the "Apostles to the Slavs".

They are credited wit ...

to Slavic Great Moravia

Great Moravia ( la, Regnum Marahensium; el, Μεγάλη Μοραβία, ''Meghálī Moravía''; cz, Velká Morava ; sk, Veľká Morava ; pl, Wielkie Morawy), or simply Moravia, was the first major state that was predominantly West Slavs, Wes ...

. By then most of the Slavic population of Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedon ...

was Christian and Tsar Boris I himself was baptized in 864. Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia (Serbian language, Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeast Europe, Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Bas ...

was accounted Christian by about 870. In early 867 Patriarch Photios I of Constantinople

Photios I ( el, Φώτιος, ''Phōtios''; c. 810/820 – 6 February 893), also spelled PhotiusFr. Justin Taylor, essay "Canon Law in the Age of the Fathers" (published in Jordan Hite, T.O.R., & Daniel J. Ward, O.S.B., "Readings, Cases, Materia ...

wrote that Christianity was accepted by the Kievan Rus'

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas of ...

, which however was definitively Christianized only at the close of the following century.

Of these, the Church in Great Moravia chose immediately to link with Rome, not Constantinople: the missionaries sent there sided with the Pope during the

Of these, the Church in Great Moravia chose immediately to link with Rome, not Constantinople: the missionaries sent there sided with the Pope during the Photian Schism

The Photian Schism was a four-year (863–867) schism between the episcopal sees of Rome and Constantinople. The issue centred on the right of the Byzantine Emperor to depose and appoint a patriarch without approval from the papacy.

In 857, Ig ...

(863–867). After decisive victories over the Byzantines at Acheloos and Katasyrtai, Bulgaria declared its church autocephalous and elevated it to the rank of patriarchate, an autonomy recognized in 927 by Constantinople, but abolished by Emperor Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

Bulgaroktonos (the Bulgar-Slayer) after his 1018 conquest of Bulgaria.

In Serbia, which became an independent kingdom in the early 13th century, Stephen Uroš IV Dušan, after conquering a large part of Byzantine territory in Europe and assuming the title of Tsar, raised the Serbian archbishop to the rank of patriarch in 1346, a rank maintained until after the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Turks. No Byzantine emperor ever ruled Russian Christendom.

Expansion of the church in western and northern Europe began much earlier, with the conversion of the Irish in the 5th century, the Franks at the end of the same century, the Arian Visigoths in Spain soon afterwards, and the English at the end of the 6th century

The 6th century is the period from 501 through 600 in line with the Julian calendar. In the West, the century marks the end of Classical Antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. The collapse of the Western Roman Empire late in the previous ...

. By the time the Byzantine missions to central and eastern Europe began, Christian western Europe, in spite of losing most of Spain to Islam, encompassed Germany and part of Scandinavia, and, apart from the south of Italy, was independent of the Byzantine Empire and had been almost entirely so for centuries.

This situation fostered the idea of a universal church linked to no one particular state. Long before the Byzantine Empire came to an end, Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

also, Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

and other central European peoples were part of a church that in no way saw itself as the empire's church and that, with the East-West Schism

East West (or East and West) may refer to:

*East–West dichotomy, the contrast between Eastern and Western society or culture

Arts and entertainment

Books, journals and magazines

*'' East, West'', an anthology of short stories written by Salm ...

, had even ceased to be in communion with it.

East–West Schism (1054)

With the defeat and death in 751 of the last

With the defeat and death in 751 of the last Exarch of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna ( la, Exarchatus Ravennatis; el, Εξαρχάτο της Ραβέννας) or of Italy was a lordship of the Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantine Empire) in Italy, from 584 to 751, when the last exarch was put to death by the ...

and the end of the Exarchate, Rome ceased to be part of the Byzantine Empire. Forced to seek protection elsewhere, the popes turned to the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

and, with the coronation of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first Holy ...

by Pope Leo III

Pope Leo III (died 12 June 816) was bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from 26 December 795 to his death. Protected by Charlemagne from the supporters of his predecessor, Adrian I, Leo subsequently strengthened Charlemagne's position b ...

on 25 December 800, transferred their political allegiance to a rival Roman emperor. Disputes between the see of Rome, which claimed authority over all other sees, and that of Constantinople, which was now without rival in the empire, culminated perhaps inevitably in mutual excommunications in 1054.

Communion with Constantinople was broken off by European Christians with the exception of those ruled by the empire (including the Bulgarians and Serbs) and of the fledgling Kievan or Russian Church, then a metropolitanate

A metropolis religious jurisdiction, or a metropolitan archdiocese, is an episcopal see whose bishop is the metropolitan bishop or archbishop of an ecclesiastical province. Metropolises, historically, have been important cities in their provinces ...

of the patriarchate of Constantinople. This church became independent only in 1448, just five years before the extinction of the empire, after which the Turkish authorities included all their Orthodox Christian subjects of whatever ethnicity in a single ''millet

Millets () are a highly varied group of small-seeded grasses, widely grown around the world as cereal crops or grains for fodder and human food. Most species generally referred to as millets belong to the tribe Paniceae, but some millets al ...

'' headed by the Patriarch of Constantinople.

The Westerners who set up Crusader states

The Crusader States, also known as Outremer, were four Catholic realms in the Middle East that lasted from 1098 to 1291. These feudal polities were created by the Latin Catholic leaders of the First Crusade through conquest and political in ...

in Greece and the Middle East appointed Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

(Western) patriarchs and other hierarchs, thus giving concrete reality and permanence to the schism. Efforts were made in 1274 ( Second Council of Lyon) and 1439 (Council of Florence

The Council of Florence is the seventeenth ecumenical council recognized by the Catholic Church, held between 1431 and 1449. It was convoked as the Council of Basel by Pope Martin V shortly before his death in February 1431 and took place in ...

) to restore communion between East and West, but the agreements reached by the participating eastern delegations and by the emperor were rejected by the vast majority of Byzantine Christians.

In the East, the idea that the Byzantine emperor was the head of Christians everywhere persisted among churchmen as long as the empire existed, even when its actual territory was reduced to very little. In 1393, only 60 years before the fall of the capital, Patriarch Antony IV of Constantinople

Antony IV (? – May 1397) was the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople for two terms, from January 1389 to July 1390, and again from early 1391 until his death.

He was originally a hieromonk, possibly from the Dionysiou monastery in Mount ...

wrote to Basil I of Muscovy

Vasily I Dmitriyevich ( rus, Василий I Дмитриевич, Vasiliy I Dmitriyevich; 30 December 137127 February 1425) was the Grand Prince of Moscow ( r. 1389–1425), heir of Dmitry Donskoy (r. 1359–1389). He ruled as a Golden Horde ...

defending the liturgical commemoration in Russian churches of the Byzantine emperor on the grounds that he was "emperor (βασιλεύς) and autokrator of the Romans, that is ''of all Christians''". According to Patriarch Antony, "it is not possible among Christians to have a Church and not to have an emperor. For the empire and the Church have great unity and commonality, and it is not possible to separate them", and "the holy emperor is not like the rulers and governors of other regions".

Legacy

Following the schism between the Eastern and Western churches, various emperors sought at times but without success to reuniteChristendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwine ...

, invoking the notion of Christian unity between East and West in an attempt to obtain assistance from the pope and Western Europe against the Muslims who were gradually conquering the empire's territory. But the period of the Western Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The best known of these Crusades are those to the Holy Land in the period between 1095 and 1291 that were in ...

against the Muslims had passed before even the first of the two reunion councils was held.

Even when persecuted by the emperor, the Eastern Church, George Pachymeres

George Pachymeres ( el, Γεώργιος Παχυμέρης, Geórgios Pachyméris; 1242 – 1310) was a Byzantine Greek historian, philosopher, music theorist and miscellaneous writer.

Biography

Pachymeres was born at Nicaea, in Bithynia, wher ...

said, "counted the days until they should be rid not of their emperor (for they could no more live without an emperor than a body without a heart), but of their current misfortunes". The church had come to merge psychologically in the minds of the Eastern bishops with the empire to such an extent that they had difficulty in thinking of Christianity without an emperor.